Method

In order to reach the chapel's ceiling, Michelangelo designed his own scaffold, a flat wooden platform on brackets built out from holes in the wall near the top of the windows, rather than being built up from the floor which would have involved a massive structure and would have meant that the chapel was unavailable for services. Mancinelli speculates that this was in order to cut the cost of timber.[14] According to Michelangelo's pupil and biographer Ascanio Condivi, the brackets and frame which supported the steps and flooring were all put in place at the beginning of the work and a lightweight screen, possibly cloth, was suspended beneath them to catch plaster drips, dust and splashes of paint.[15] Only half the building was scaffolded at a time and the platform was moved as the painting was done in stages.[14] The areas of the wall covered by the scaffolding still appear as unpainted areas across the bottom of the lunettes. The holes were re-used to hold scaffolding in the latest restoration.

Contrary to popular belief, he painted in a standing position, not lying on his back. According to Vasari, "The work was carried out in extremely uncomfortable conditions, from his having to work with his head tilted upwards".[9] Michelangelo described his physical discomfort in a humorous sonnet accompanied by a little sketch (see section Quotations).

The painting technique employed was fresco, in which the paint is applied to damp plaster. Michelangelo had been apprenticed in the workshop of Ghirlandaio, one of the most competent and prolific of Florentine fresco painters, at the time that the latter was employed on a fresco cycle at Santa Maria Novella and whose work was represented on the walls of the Sistine Chapel.[16] At the outset, the plaster, intonaco, began to grow mold because it was too wet. Michelangelo had to remove it and start again. He then tried a new formula created by one of his assistants, Jacopo l'Indaco, which resisted mold, and entered the Italian building tradition.[15]

Because he was painting fresco, the plaster was laid in a new section every day, called a giornata. At the beginning of each session, the edges would be scraped away and a new area laid down.[14] The edges between giornate remain slightly visible, thus they give a good idea of how the work progressed. It was customary for fresco painters to use a full-sized detailed drawing, a cartoon, to transfer a design onto a plaster surface – many frescoes show little holes made with a stiletto, outlining the figures. Here Michelangelo broke with convention; once confident the intonaco had been well applied, he drew directly onto the ceiling. His energetic sweeping outlines can be seen scraped into some of the surfaces,[nb 1] while on others a grid is evident, indicating that he enlarged directly onto the ceiling from a small drawing.

Michelangelo painted onto the damp plaster using a wash technique to apply broad areas of colour, then as the surface became drier, he revisited these areas with a more linear approach, adding shade and detail with a variety of brushes. For some textured surfaces, such as facial hair and woodgrain, he used a broad brush with bristles as sparse as a comb. Altogether, Michelangelo's techniques show the skill that one would expect of Ghirlandaio's greatest pupil. He employed all the finest workshop methods and best innovations, combining them with a diversity of brushwork and breadth of skill far exceeding that of the meticulous Ghirlandaio.[nb 2]

The work commenced at the end of the building furthest from the altar, with the latest of the narrative scenes, and progressed towards the altar with the scens of the Creation.[12] The first three scenes, from the story of Noah, contain a much larger number of small figures than the later panels. This is partly because of the subject matter, which deals with the fate of Humanity, but also because all the figures at that end of the ceiling, including the prophets and Ignudi, are smaller than in the central section.[17] As the scale got larger, Michelangelo's style became broader, the final narrative scene of God in the act of Creation was painted in a single day.[18]

The bright colours and broad, cleanly defined outlines make each subject easily visible from the floor. Despite the height of the ceiling the proportions of the Creation of Adam are such that when standing beneath it, "it appears as if the viewer could simply raise a finger and meet those of God and Adam". Vasari tells us that the ceiling is "unfinished", that its unveiling occurred before it could be reworked with gold leaf and vivid blue lapis lazuli as was customary with frescoes and in order to better link the ceiling with the walls below it which were highlighted with a great deal of gold. But this never took place, in part because Michelangelo was reluctant to set up the scaffolding again, and probably also because the gold and particularly the intense blue would have distracted from his painterly conception.[9]

Some areas were, in fact, decorated with gold: the shields between the Ignudi and the columns between the Prophets and Sibyls. It seems very likely that the gilding of the shields was part of Michelangelo's original scheme since they are painted to resemble a certain type of parade shield, a number of which still exist and which are decorated in a similar style with gold.

Section reference.[9][14][15][19]

Content

The overt subject matter of the ceiling is the doctrine of humanity's need for Salvation as offered by God through Jesus. It is a visual metaphor of Humankind's need for a covenant with God. The old covenant of the Children of Israel through Moses and the new covenant through Christ had already been represented around the walls of the chapel.[2]

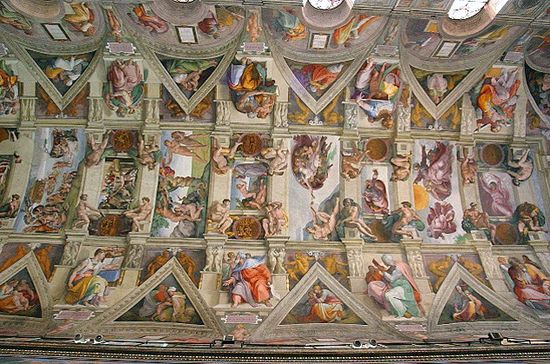

The main components of the design are nine scenes from the Book of Genesis, of which five smaller ones are each framed and supported by four naked youths or Ignudi. At either end, and beneath the scenes are the figures of twelve men and women who prophesied the birth of Jesus. On the crescent-shaped areas, or lunettes, above each of the chapel's windows are tablets listing the Ancestors of Christ and accompanying figures. Above them, in the triangular spandrels, a further eight groups of figures are shown, but these have not been identified with specific Biblical characters. The scheme is completed by four large corner pendentives, each illustrating a dramatic Biblical story.[17]

The narrative elements of the ceiling illustrate that God made the World as a perfect creation and put humanity into it, that humanity fell into disgrace and was punished by death and by separation from God. Humanity then sank further into sin and disgrace, and was punished by the Great Flood. Through a lineage of Ancestors – from Abraham to Joseph – God sent the saviour of humanity, Christ Jesus. The coming of the Saviour was prophesied by Prophets of Israel and Sibyls of the Classical world. The various components of the ceiling are linked to this Christian doctrine.[17] Traditionally, the Old Testament was perceived as a prefiguring of the New Testament. Many incidents and characters of the Old Testament were commonly understood as having a direct symbolic link to some particular aspect of the life of Jesus or to an important element of Christian doctrine or to a sacrament such as Baptism or the Eucharist. Jonah, for example was readily recognisable by his attribute of the large fish, and was commonly seen to symbolised Jesus' death and resurrection.[3]

While much of the symbolism of the ceiling dates from the early church, the ceiling also has elements that express the specifically Renaissance thinking which sought to reconcile Christian theology with the philosophy of Humanism.[20] During the 15th century in Italy, and in Florence in particular, there was a strong interest in Classical literature and the philosophies of Plato, Socrates and other Classical writers. Michelangelo, as a young man, had spent time at the Humanist academy established by the Medici family in Florence. He was familiar with early Humanist-inspired sculptural works such as Donatello's bronze David, and had himself responded by carving the enormous nude marble David which was placed in the piazza near the Palazzo Vecchio, the home of Florence's council.[21] The Humanist vision of humanity was one in which people responded to other people, to social responsibility and to God in a direct way, not through intermediaries, such as the Church.[22] This conflicted with the Church's emphasis. While the Church emphasized humanity as essentially sinful and flawed, Humanism emphasized humanity as potentially noble and beautiful.[nb 3] These two views were not necessarily irreconcilable to the Church, but only through a recognition that the unique way to achieve this "elevation of spirit, mind and body" was through the Church as the agent of God. To be outside the Church was to be beyond Salvation. In the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo presented both Catholic and Humanist elements in a way that does not appear visually conflicting. The inclusion of "non-biblical" figures such as the Sibyls or Ignudi is consistent with the rationalising of Humanist and Christian thought of the Renaissance. This rationalisation was to become a target of the Counter Reformation.

The iconography of the ceiling has had various interpretations in the past, some elements of which have been contradicted by modern scholarship[nb 4] and others – such as the identity of the figures in the lunettes and spandrels – continue to defy interpretation.[23] Modern scholars have sought, as yet unsuccessfully, to determine a written source of the theological program of the ceiling, and have questioned whether or not it was entirely devised by the artist himself, who was both an avid reader of the Bible and a genius.[24] Also of interest to some modern scholars is the question of how Michelangelo's own spiritual and psychological state is reflected in the iconography and the artistic expression of the ceiling.[nb 5]

Architectural scheme

Real

The Sistine Chapel is 40.5 metres long and 14 metres wide. The ceiling rises to 20 metres above the main floor of the chapel. The vault is of quite a complex nature and it is unlikely that it was originally intended to have such complex decoration. Pier Matteo d'Amelia provided a plan for its decoration with the architectural elements picked out and the ceiling painted blue and dotted with gold stars, similar to that of the Arena Chapel decorated by Giotto at Padua. [25]

The chapel walls have three horizontal tiers with six windows in the upper tier down each side. There were also two windows at each end, but these have been closed up above the altar when Michelangelo's Last Judgement was painted, obliterating two lunettes. Between the windows are large pendentives which support the vault. Between the pendentives are triangularly shaped arches or spandrels cut into the vault above each window. Above the height of the pendentives, the ceiling slopes gently without much deviation from the horizontal.[25] This is the real architecture. Michelangelo has elaborated it with illusionary or fictive architecture.

Illusionary

The first element in the scheme of painted architecture is a definition of the real architectural elements by accentuating the lines where spandrels and pendentives intersect with the curving vault. Michelangelo painted these as decorative courses that look like sculpted stone moldings.[nb 6] These have two repeating motifs, a formula common in Classical architecture.[nb 7] Here, one motif is the acorn, the symbol of the family of both Pope Sixtus IV who built the chapel and Pope Julius II who commissioned Michelangelo's work.[nb 8][26] The other motif is the scallop shell, one of the symbols of the Madonna, to whose assumption the chapel was dedicated in 1483.[nb 9][27] The crown of the wall then rises above the spandrels, to a strongly projecting painted cornice that runs right around the ceiling, separating the pictorial areas of the biblical scenes from the figures of Prophets, Sibyls and Ancestors, who literally and figuratively support the narratives. Ten broad painted crossribs of travertine cross the ceiling and divide it into alternately wide and narrow pictorial spaces, a grid which gives all the figures their defined place.[28]

A great number of small figures have been integrated with the painted architecture, the purpose of which appears to be purely decorative. These include two faux marble putti below the cornice on each rib, each one a male and female pair; stone rams-heads are placed at the apex of each spandrel; copper-skinned nude figures in varying poses, hiding in the shadows, propped between the spandrels and the ribs like animated bookends; and more putti, both clothed and unclothed strike a variety of poses as they support the nameplates of the Prophets and Sibyls.[29] Above the cornice and to either side of the smaller scenes are an array of round shields, or medaillons. They are framed by a total of twenty more figures, the so-called Ignudi which are not part of the architecture, but sit on inlaid plinths, their feet planted convincingly on the fictive cornice. Pictorially, the Ignudi appear to occupy a space between the narrative spaces and the space of the chapel itself. (see below)

No comments:

Post a Comment